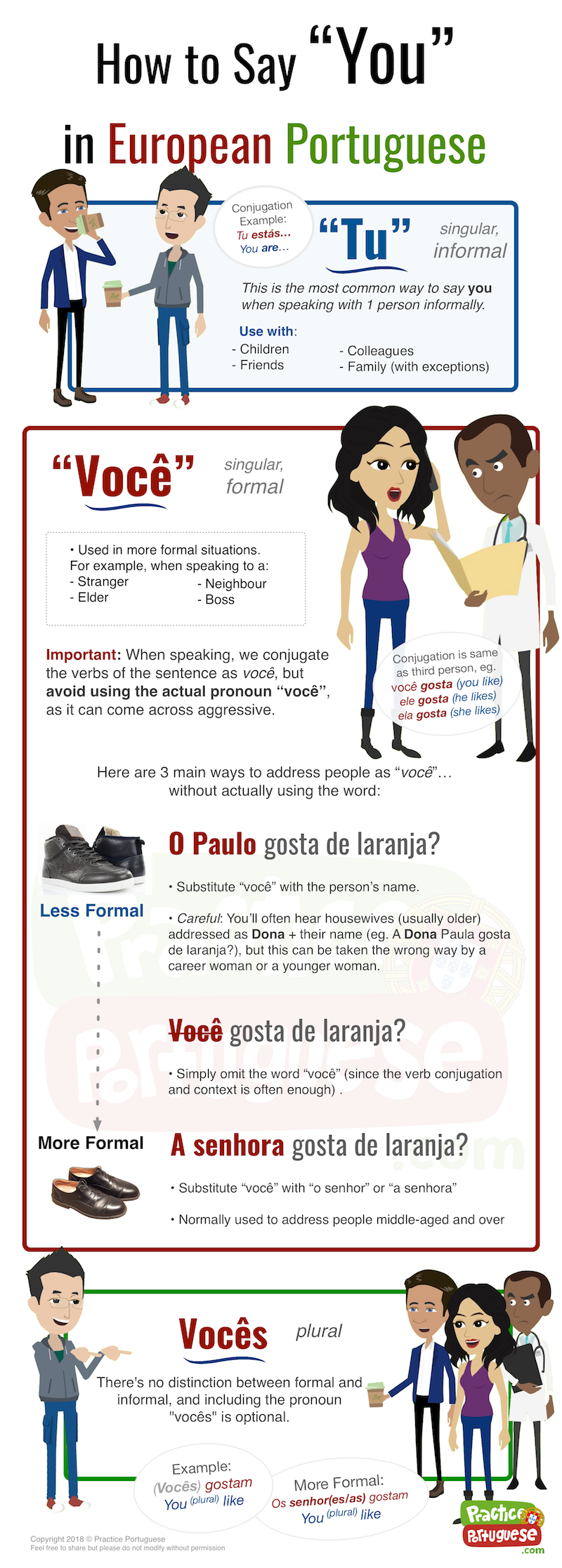

As part of our Tu e Você unit, this guide will cover how to address people formally vs. informally in Portugal, with a special focus on the difference between tu and você in European Portuguese.

Grammatically, it doesn’t take too long to learn the basics. The most challenging aspects for estrangeirosforeigners , however, tend to be those that have to be made on a social level. For example, you must determine not only when it’s best to speak to someone formally, but also choose between the subtle variations of which formal language to use.

Even the natives (like Rui! 🇵🇹) have a hard time dissecting some of these unspoken social rules, but our aim is to make this the definitive European Portuguese resource for informal vs. formal language, and all the grey areas in between!

It’s important to be aware of the difference between tu and você from the beginning, but don’t worry if you don’t have it perfected right away. It goes without saying that it will take many months or even years of experience to get comfortable with all these social subtleties.

The Different Forms of “You”

You don’t have to worry about formality in the 1st person or 3rd person (yay!). But it gets a little trickier in the 2nd person, which has formal and informal variations.

As we mentioned, the two main pronouns used for speaking directly to someone are: tuyou (informal) and vocêyou (formal)

You – Informal

When speaking to someone informally, we use the pronoun tuyou (inf.)

Tu trabalhas muito.You (inf.) work a lot.

This is mostly used with friends, colleagues, children, and family.

You – Formal

To speak to someone formally, we use different forms of vocêyou (formal)

Você trabalha muito.You (formal) work a lot.

With você, the verbs are conjugated exactly the same as with third person pronouns (ele and ela). It’s almost as if you’re referring to another person, even though you’re speaking directly to someone!

This seems pretty simple so far, but unfortunately, treating someone formally in Portugal isn’t as easy as just swapping out tu and você. We’ll discuss these complexities in more detail below.

Note: This highlights a big difference between Brazilian Portuguese and European Portuguese, as Brazilians use você in informal situations as well. When Brazilians want to speak more formally, they use o senhorsir, you(formal,masc.) or a senhoramadam, you(formal,fem.) . As you’ll see below, this is also an option in European Portuguese, when you want to be very formal.

You – Plural (Speaking to Multiple People)

The pronoun used to speak to a group is vocêsyou (plural) . Even though you are talking to other people, the verb is conjugated exactly the same as the 3rd person plural.

Vocês trabalham muito.You (pl.) work a lot.

Don’t be fooled – it looks very similar to the singular pronoun você, but the plural pronoun vocês does not carry the same formality. There’s not really a clear distinction between formal and informal when talking to a group, so it’s typically fine to use vocês in both contexts. That said, if you want to make sure you’re being very formal, you can use as senhorasthe ladies or os senhoresthe sirs, the gentlemen .

Os senhores trabalham muito.You (pl.,masc.,formal) work a lot.

Just like we mentioned with the other pronouns, when the context is clear, it’s common to drop vocês or os senhores/as senhoras and just start with the conjugated verb:

Trabalham muito.You (pl.) work a lot.

The Many Forms of Você

Now that we’ve reviewed the basics of tu, você, and vocês in European Portuguese, it’s time to explore some of the hidden complexity behind você.

The tricky part is that Portuguese natives usually avoid using the actual pronoun você whenever possible. Calling someone você to their face can come across as a bit aggressive or direct, kind of like pointing at someone for emphasis while saying “you”. That would be a bit intense, right? Instead, different “forms” of você are used. But don’t worry: the verbs are conjugated exactly the same as if você were present in the sentence, so the grammar will be consistent.

Keep in mind that most Portuguese natives will be very understanding that you are a foreigner doing your best to learn the language. They will have already had exposure to Brazilian immigrants and soap opera stars using você frequently, so they are less likely to be offended, compared to if they were speaking to a native.

But we know you don’t need any estrangeiro handicap! In the spirit of learning as much as we can about the language and Portuguese culture, let’s explore the following infographic to find out how the Portuguese use você… without saying você!

A Closer Look

Let’s take a closer look at those 3 main variations of você from the infographic, so you know which to choose when speaking to someone formally. We’ll go in order from least to most formal.

1) Replace você with the person’s first name

O Paulo gosta de viajar?Do you (formal, Paulo) like to travel?

O Paulo gosta de viajar?Do you (formal, Paulo) like to travel?

When to use:

- When the informal tu would be inappropriate, but you also don’t want to be too formal. Obviously, you can only use this once you already know the person (because you’ll need to know their first name).

- You probably could speak to them informally, but aren’t 100% sure and don’t want to catch them off guard. (If they’re friendly, they may later invite you to treat them as tu):

Podes tratar-me por tuYou (inf.) can treat me as you (informal)

Vamos tratar-nos por tuLet's treat each other as you (informal)

- This form can be used with a work colleague who is either of a higher ranking than you, or of the same ranking but much older.

- This is also a good way to treat the adult family members of your friends, as it shows respect but also some warmth at the same time, as you’re making the effort to use their name.

- Although most families use tu with each other, more traditional or formal families may use this version of você for every situation: between friends, relatives, children, and sometimes even the family dog! If this is the case, you would hear the relation (a Avó, o Avô, o Filho, a Mãe, etc. – Grandma, Grandpa, Son, Mother, etc.) in place of você or the person’s first name.

What about “Dona”?

Housewives are often addressed as Dona + their first name, but never use Dona + their surname. (This is an important distinction from English, where we would usually use Mrs. + surname). While you will hear this sometimes, it may be best to steer clear of using it as a beginner, as you’re more likely to accidentally offend someone compared to the other options.

Como vai, Dona Fernanda?How is it going, Mrs. Fernanda?

2) Replace você with… nothing!

Gosta de ler?Do you (formal) like to read?

Gosta de ler?Do you (formal) like to read?

When to use:

- If you could use variation #1, but don’t yet know the person’s name

- If you’re speaking to a stranger, but don’t want to sound overly formal / distance yourself. Example: When asking a stranger for directions who isn’t significantly older than you, you’d probably use this variation.

- When speaking to any kind of attendant, such as at a cafe or supermarket

But wait? If we take away você, how will they know who I’m talking to?!

- The key is learning to rely on context. For example, if you say Gosta de ler? it could mean “Do you like to read?”, “Does he like to read?”, or “Does she like to read?”

- Had you just mentioned another person in the conversation? Yes? Then the listener will probably know you are referring to that other person.

- Are you speaking directly to someone you just met and have been asking them questions about themselves? Yes? Then the listener probably knows you are referring to them (the listener), but in a formal way.

3) Replace você with o senhor / a senhora

A senhora gosta de ler?Do you (formal,fem.) like to read?

A senhora gosta de ler?Do you (formal,fem.) like to read?

When to use:

- When you want to maintain a professional/social distance from the person

- If you want to recognize their higher seniority compared to yourself, either in age or status

- If you are talking to a stranger and the situation is more intense (eg. a confrontation, car accident etc.), this lets you be firm and respectful at the same time.

- In general, any time you want to be absolutely sure that you’re showing respect, you can’t go wrong with using o senhor/a senhora.

4) Replace você with their professional title

We didn’t include this one in the chart since the circumstances for this level of formality are rare. When someone is a professor in an official institute (as well as having their doctorate), they are treated as Professora Doutora if they are female, or Professor Doutor if they are male.

Obrigado, Doutora AnaThank you, Dr. Ana

Parabéns pelo doutoramento, Doutora FernandaCongratulations on your doctorate, Doctor Fernanda

Adding SenhorSir or SenhoraMadam before the title will make this treatment even more formal:

É uma honra conhecê-la, Senhora Professora AnaIt's an honour to meet you, Mrs. Professor Ana

When to use:

- Colleagues of certain high-level professions may also be required to treat each other this way on the job.

- Speaking to professors in any academic situation. University teachers can be addressed as Professor Doutor for additional formality.

- Used in very formal circumstances, outside a classroom environment, if the person has an academic title.

- The title doutor / doutora is often abused in European Portuguese. Rather than being reserved for people with PhDs, it is sometimes used to refer to anyone who is assumed to have any kind of post-secondary education. However, if they do not have a PhD / doctorate, the term is usually abbreviated to “Dr.” or “Dra.”.

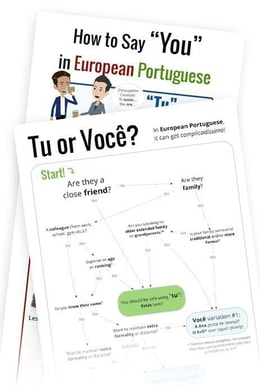

The Ultimate Tu vs. Você Flowchart!

Download the Featured PDF for free below

We hate spam and guarantee you 100% privacy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

We hate spam and guarantee you 100% privacy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

As you know, everything in life is more exciting when it’s tediously distilled into a flowchart. 😉 We put together the ultimate cheat sheet for you to print or save to your mobile device, to refer back to throughout your Portuguese adventures! You can view the graphic below, or use the form above to download everything in a high-quality, printable PDF. When you’re ready, continue on to the next lesson in this unit to practice using tu and você in phrases.

Download PDF

Download PDF

Interesting!! Somewhat like the Germans. German was my original foreign language and I worked there for some time and struggled with Du and Sie, which are the Tu and Voce equivalent. I particularly recall meeting a young German on a family holiday and using Sie, as I did not know how old he was (things change around 14/15 if they are strangers; different if children of family friends). I was firmly told by said child that I might use Du with him! The other occasion was being invited to visit a work friend and meeting his parents, several times, including when I stayed overnight. The Mother used Du to me – as friend of her son/family I guess – but my friend said that that did NOT allow me to call her or the father Du. I had to stick to Sie, as more correct.

None of it easy, but I do understand the Portuguese system a little for that reason. Go for the more respectful/formal until you can see it is safe to do otherwise or are invited so to do. I had to invite our German agent to use DU, even though he was older than me, as I was effectively his employer.

Lots of fun

Keep up the good work!!

Martin

Martin’s comment about German usage is interesting.

It is similar in my native Norwegian, though in the modern time it is being blurred a little.

DE is/was used in formal situations “Tror de det?” Do you think so?

DU is/was used in intimate situations (family, friends, etc.) Hvad synes du? What do you think?

Harald

yeah for german speakers, it is quite easy to understand the parts about formal and informal.

In German everything is much easier. When du is not appropriate, you have to use Sie, and you actually say “Sie könnten…”. You don’t have to replace it with “Die Frau XX könnte” or just say “könnte” with zero clarity who you are referring to. Even though telling the difference is not a problem, the idea to avoid você is the real problem.

Thank you. That is really helpful. Many years later I am still often confused. For us english speakers this is a minefield!

My question is about when you say ”Vamos tratar-nos por tu?”. Does the initiative have to be taken by the person with seniority in term of age or status? Can you give me some guidelines on how long before you can go to tu in a new friendship between equals.

Great site!

Thanks for the kind words, glad you’re liking the site! Great question – it’s a good idea to play it safe and wait for the other person to suggest (or initiate) the informal treatment, especially if they have seniority. But in some situations, you might sense that the conversation is quite casual, with occasional slang or a frank tone… or perhaps there is no clear sense of, or need for seniority. You might even start feeling awkward treating a person formally with the direction the conversation is going. These may be the right moments to suggest the informal treatment.

Here’s an example: You’re in a classroom with someone a generation older than you, so you carefully default to interacting with them formally. After a few minutes, you start talking a bit about challenges of the lesson and build a friendly rapport, which diminishes the importance of the age gap – it becomes simply a conversation between two colleagues at the same level, with similar challenges. Your classmate may appreciate the suggestion that you treat each other as “tu”, since it shows you seem them as an equal rather than an older person. (Obviously, this could backfire if you read the situation wrong).

Navigating these situations can be overwhelming for a foreigner, but try not to worry – it will always be clear to the other person that we’re doing our best as non-natives, and they will likely be gracious and forgiving at the odd misstep. The best we can do is watch other people’s examples and gain experience reading these situations over time.

Obrigado! Muito útil!

Só uma pergunta. Na frase “É uma honra conhecê-lo, Senhora Professora Ana”, ‘conhecê-lo’ não deveria ser ‘conhecê-la’?

Continuem com o bom trabalho!

David

Olá David, thanks for your support! Great job catching that typo – it’s now corrected. Thanks again 🙂

I’ve been away from PP for about a month with a health issue. Your new “discuss” feature is terrific. I’m amazed as to how often your team adjusts to changes and requests. It’s like having a personal tutor. Well done!

Oh no, I hope you have a quick recovery and are back in full force soon! Thanks for your ongoing support, we’re glad to have you with us 🙂

Thanks for letting us know! Fixed 🙂

Obrigado pela informação que é muito útil.

This and other explanations on the site are excellent. I am new to this site but in a matter of days has given me a greater insight into the intricacies of the language in Europe.

I am not a novice in Portuguese but I wanted to concentrate on European Portuguese. I am in Portugal three or four times every year but only very occasionally in Brazil.

I am so pleased to be with you. The language you teach is usable and useful and so far worth every cent!

Thanks so much for your kind words and support, it’s great to have you with us as of these last couple days. Keep the feedback coming 🙂

Eu precisei essa muito boa licão. Esto tema é difícil para mim. Quando eu morei no brasil (1973) e foi professor visitante na

Universidade de São Paulo, eu não tinha que usar “tu”. Usei “vocé” com todo exceto por minha familia e eles falaram ingles. Não aprendei nenhum verbos de segunda pessoa informal. Agora em Portugal preciso.

Great lessons! Luckily this is all very similar to Italian etiquette … only joined a few days ago… loving your work! Thank you!

Thanks so much for your kind words and support, Giusi!

Great charts . really clarified the question for me. Obrigado

I feel so much more confident about how the language works now! We loved in Lisboa for 3 years and I was winging it. We are about to go back there to live and I cannot wait to put my new Portuguese learning into practice! This is HANDS DOWN the BEST learning tool for the European Portuguese Language I have ever used. BRAVO!!

Thanks for your kind words! Glad to be a part of your journey 🙂

Really enjoying the course. Not too easy – not too hard!

My name is Donna and I’m 69. People are actually going to call me Dona Donna with straight faces?

Also, I still don’t fully grasp why and when i used Desculpe versus Desculpa, other than one’s formal and one’s informal, but my understanding of formal versus informal always leads me to use the wrong one. So I go through this process of “Which one? It’s informal, so it’s XXX, but I’m always wrong when I try to think it through, so I’d better go with Y”. Can anyone tell me something that will help?

They just might, Dona Donna! 🙂

With adults in general, you would use “Desculpe” (formal) with anyone you would address as ‘você’/’o senhor’/’a senhora’/’a dona’, and “desculpa” (informal) for anyone you can talk to casually. If in doubt, stick to “Desculpe”. With children, teenagers and even young adults, you can just say ‘Desculpa’ all the time.

My problem is that when I think voces, I don’t think either an e or an e ending. I think an m ending. For a or e, I think a single male or female person. Those endings just don’t make sense to me, though I’m sure there is reason for them. I don’t easily learn things that go against general concepts that I’ve already learned. I need to know WHY those are the appropriate endings.

Ah, but ‘vocês’ is plural. In that case, you only have one option, ‘Desculpem’, so you’ll never get it wrong there. ‘Desculpe’ and ‘desculpa’ are only used when addressing a single person, but the choice of ending isn’t determined by the person’s gender, only by the level of formality you wish to use with them, as I explained in my previous comment. And why is it this way and not some other way?

Maybe it helps if you think about the conjugation of the verb ‘desculpar’ in the imperative mood. ‘Desculpa’ is the second-person singular (tu) conjugation, and ‘desculpe’ is a third-person singular (você) conjugation. Note that ‘você’ is a formal second person, but conjugated as a third person.

Ah, I thought it was more or less like the royal “we”, and so treated as if it was plural even though it was singular, so that helps some.

Americans are very forthright when meeting people by introducing themselves and announcing their name. I have found in the region we live in, the Beira Alta, people do not introduce themselves. I don’t know if they are shy around foreigners or this is a hold-over from the Salazar era where people were nervous about being identified, but it gets very awkward after a while when dealing with someone over time and you don’t want to say “voce” to their face or to demand to know their name. And when it comes to professional or trades people, it seems to us as downright unprofessional. We sometimes feel that the poor customer service we sometimes encounter in otherwise modern businesses is related to this lack of forthright interaction. Any advice?

You’re right, Portuguese people won’t always bother to introduce themselves when talking to strangers. I’m sure this isn’t unique to Portuguese people and I wouldn’t read too much into it 🙂 Probably just one of those unavoidable cultural differences between the two sides of the Atlantic. If you’re really intent on breaking the ice a bit further, you can always lead by example and introduce yourself first. Then ask the other person their name, if they don’t say it spontaneously. It might be unexpected for people, but I doubt anyone would consider it rude or refuse to answer.

This is by far the most comprehensive explanation I have come across. Excellent work

According to the flowchart it is never necessary to use você.

Different Portuguese speakers may have slightly different opinions about ‘você’. I would say that the younger the person you talk to, the lower the risk of potentially offending them by addressing them directly as ‘você’ – but the risk is already low from the start. In any case, I can’t think of a situation where it’s ever truly necessary to say the word, no. You still have to be aware of it to form grammatically correct sentences 🙂

Having Dutch as my mother tongue and also speaking German and French (sorry for showing off), I have noticed over recent decades that with all these languages people are becoming less and less formal. The Dutch prime minister nowadays even addresses the population with “tu” on TV.

Is this also a tendency in Portugal or do the Portuguese remain more rigid in the way they address each other?

I’d say that the Portuguese in general continue to adhere to formal language whenever expected 🙂 Politicians, in particular, are always very formal and verbose!

I’m volunteering at a farm shop and meeting lots of people with whom it seems more appropriate to use você and struggle to reply to ‘como está?’ without using ‘você’ in the reply, any tips?

Sure! You can use “o senhor” or “a senhora” instead of “você”, as the flowchart recommends for strangers you need to address formally 🙂 For example, “Q: Como está? A: Eu estou bem, e a senhora?”.

Very good

I am currently staying a few months in Algarve. How should I address the lady who is cleaning the apartment twice a week? “Não precisa limpar o quorto hoje”, I quess a senhora is not possible, neither você?

Olá! “Não precisa de limpar o quarto hoje” is perfect 🙂 But you can also start with “a senhora” if you’d like. Better yet, use her given name formally, e.g. “A Fernanda não precisa de limpar o quarto hoje”. This is still polite, while also acknowledging the relative familiarity between you, since she comes regularly every week.

My biggest problem with learning a new language is retaining the information! Since I am 2/3rds through the seventies! However I find I must keep reviewing the lessons. This could be a long haul, but I do like the way you are presenting the learning and very clearly identifying the process. Thank you.

Excellent

This is so helpful, my partner and I have been struggling with this as to what to use from observation….and its not easy! I’m sure we will continue to make gaffes, but as you say, the people are forgiving and we will keep trying. Muito obrigada.

Aha! Thank you for this! My Portuguese partner has not been able to clearly explain why I should neither use ‘voce’ nor ‘tu’ when addressing his family members. He did say once it would ‘not be weird’ for me to address his older brother (who we hang out with in a friendly and casual manner) with the third person, so: formal, just not explicitly formal. I guess this is what he meant: I can best use ‘o Pedro + third person verb??

Indeed I have heard them use each other’s names quite a lot, and mine too. But i have always interpreted it as third person and (being Dutch) to me that sounds as though they were speaking about someone in front of them, and honestly it seemed slightly rude. Come to think of it, this also means I don’t usually respond myself when they ask something like ‘did (the) Evelien enjoy the trip today …?’ – I would assume they were asking my partner instead of me, because my Portuguese was not yet good enough to talk directly at me. While maybe actually they were trying to include me in the conversation… whoops! I hope we can make it to Portugal again this year, so I can practise and maybe even initiate some conversations…

That’s a great story! At least now you have a bit more clarity on this whole thing 🙂

A question about grammatical terminology. The section on Vocês is titled “Speaking to Multiple People (Third person plural)”. Shouldn’t it be “second person plural”? I understand that the verb conjugation is the same as third person plural (eles/elas), but vocês is still 2nd person, no? Or am I misunderstanding something?

You’re right, it is technically 2nd person plural when you are speaking to multiple people and 3rd person plural when speaking about multiple other people. Since vocês forms are conjugated the same as the 3rd person plural, sometimes we just group it into that category for simplicity’s sake. In this case, however, it does sound misleading to include “3rd person plural” in the heading, especially when that section is only about vocês. I made some changes that will hopefully make it more clear/accurate. Thanks for pointing this out!

Now I finally understand why everyone immediately seems to remember my name here in Portugal, even after meeting me just once. I need to work on my own name memory it seems.

One question:

When formally addressing a mixed group, one would use “os senhores”, correct?

Haha, yes 🙂 About your question, personally, in very formal contexts, I would recommend really specifying “os senhores e as senhoras”. Also, “vocês” is still an option -> it’s neutral enough in terms of formality.

Oh, I wish os senhores had been around when I need os senhores in 2012. 😉

That was the year that I was visiting my father in Portugal and he had a heart attack. Only one person in the family was allowed to visit him in the ICU, and being his closest family, my tios appointed me. In my limited usage of Portuguese, we used voce for our family elders. I didn’t really have exposure to other Portuguese people. So when Dad was in the hospital and I had to talk to the doctor, she clearly bristled when I referred to her as voce. I never knew it was like pointing at someone either! Later I went to my cousin and asked, “Can you use voce when speaking to a doctor?” She said, “Absolutely not! You can’t!” I said, “I did.” She looked horrified and said, “You mustn’t!” “Too late,” I told her. As I practiced using a “senhora doutora” I had this sensation that it was getting in the way of my ability to communicate clearly, like it was creating barrier, with the doctor. It was as though we were talking about other people: “A senhora doutora pensa que o pai precisa de…” I also had this feeling that maybe the doctor didn’t like my American attitude about asking doctors a lot of questions, or maybe it was because I had offended her with my voce.

Thank you guys for yet another valuable lesson. (sorry I couldn’t use the circumflex for voce on my chromebook).

Thank you for your comment and for sharing that story. All of these formalities and titles do seem to interfere more than they help, sometimes. I hope your father still got the care he needed at the time.

Freakin’ love the flow chart, os senhores 🙂

Thank you for your comment! Ainda bem que a senhora gosta 🙂

realy enjoyed the corse

Hi Really enjoying learning with PP, it’s brilliant. I have a question. I was in the supermarket the other day and an older (lady) customer called the girl behind the fish counter ‘menina’ ie girl – before her question (about the fish). I thought this sounded quite rude, but at the end she said ‘obrigada menina’ too. So is that an acceptable way to address someone who is serving you? Thank you for taking the time to answer all our questions!

Olá! Don’t worry; when it comes from a much older person (of any gender), calling a young woman “menina” usually isn’t considered rude in any context, unless something in the person’s tone or attitude makes it so. It actually sounds rather motherly/fatherly, so it can be endearing 🙂 It would be more odd if there was no significant age difference.

I’m addressed as “menina” all the time in Portugal as a woman in my 30s. At first I was little confused about it and found it off-putting, until I learned that I should just interpret it as “Miss”. Now I’ve started to prefer being called menina, just like being called “Miss” makes one feel younger than being called “Ma’am”. I feel like this issue could be included someplace in the introductory lessons on this site.

Thank you! I shall see it this way in future!

Just a quick, silly question. In restaurants where the staff are friendly, efficient…and you want the bill/check/conta …..

How do you address them ? O senhor/A senhora ? I normally just do the usual air writing sign as a request for the bill…or say “A conta por favor”…but if I’m struggling to get a waiters attention is

there a more polite way of requesting it ?

Olá, Steve! You have a number of options, but when I want to get their attention, I usually just raise my hand where/when I know they’ll see it and say “Desculpe” (sorry/excuse me), followed by my request:

– Desculpe! A conta, por favor.

– Desculpe! É para pagar a conta, por favor.

– Desculpe! Pode trazer a conta, por favor?

– Desculpe! Poderia trazer a conta, por favor?

– etc.

All of these are absolutely fine and polite, but the last two would be the extra proper options.

Many thanks Joseph. Appreciate the prompt response.

Something to worry about when I can actually speak portuguese or actually understand what a Portuguese is saying, its very tough for me

I have a question about Dona. If I was to visit the office of a friend and I know his PA’s name, and know her a bit from visiting quite often, how would I address her? My father, who is Portuguese and in his 80s said I should call her Dona Maria, but my Portuguese friend said Dona these days is only used for cleaners and similar. I see in your lesson, you say Dona is only used for housewives (of which there are surely very few left since everyone works these days). As you say in English it’s much simpler, I would just address her as Mrs da Silva. But it feels far too formal to say a senhora, and too informal and weird not to use her name and just go with the você form of the verb, especially if I’m saying something like good morning as my opener.

Olá, Marina! “Dona” is rather tricky. It’s not exclusive to housewives, but nowadays it’s more common among them and among people in domestic jobs, so to speak (nannies, housekeepers, cleaners…, like your friend said). It’s used more for middle-aged or older women. If your friend’s PA is in that age group and other people also address her that way, then it should be fine for you to do it too. But you might just as well use her first name along with ‘você’ conjugations, just like you said. It remains polite and proper, while still acknowledging the familiarity between you two 🙂 For example, “Bom dia, Maria, como está?” (Good morning, Maria, how are you?).

There is a typo in the “A Closer Look” section above. The sentence “Obviously, you can only use this once already know the person” should be “Obviously, you can only use this once *you* already know the person”.

About the lesson itself, although I understand the concept of this formal/informal way of addressing people, as a Canadian it is all so foreign. We’re very friendly people and would never be offended in any of the many examples posted above. Learning these rules won’t come easily and I’ll probably offend many people as I struggle to learn the language.

HI! I have a question about the conjugations of the verbs with hyphens. Are there any rules we can apply to? Thanks.

Yes, you will learn more about these in the Reflexive Verbs and Clitic Pronouns units. Check out the learning notes in those units to get a preview. To sum it up briefly, those hyphenated pieces are pronouns that indicate who/what the verb refers to. So in the example “Podes tratar-me por tu”, the -me refers to the 1st person singular eu (I, me). In the example “É uma honra conhecê-la…”, the -la is the 3rd person formal feminine form, so it indicates “you” when speaking to a female in a formal way. I hope that helps! This is a more advanced topic, so don’t worry if it doesn’t make sense right away. It’s good to be aware of it, though, since these are used frequently. 🙂

W H E W ! THANK YOU THANK YOU

THANK YOU THANK YOU

🐶”/”

“Peeve” is wagging his tail! 😉

Excellent explanation!

Loving this program; thank you so much!

I have yet to see a person’s surname used in conversation. Is it ever? How about in formal written correspondence?

Thank you!

Thanks for your comment, Ruth! 🙂

We don’t really have the English tradition of saying “Mr/Mrs [Surname]”, unless the person is commonly known by just their surname. In any context, including formal written correspondence, you’ll probably only see the person’s surname if the full name (or first & last name) is being mentioned.

Obrigada for your explanation and the chart! Loving it too as the rest of the members. 🙂

Interesting. In English we have the use of the third person form for formality such as: “Would Her Majesty care to be seated?”…(it would be terribly bad manners to address the queen as ‘you’)…”Does His Lordship like his tea to be with milk?”…etc…Remembering that I think makes the degrees of formality in Portuguese a little more understandable. Sadly, we have lost our familiar ‘thou’ form, just like most of Brazil it seems.

We have not learned how to conjugate the verbs in different persons. The conjugation in Portuguese seems to be complicated.

Sorry for the confusion! Verb conjugation in different persons for ser, ir, and regular verbs (in the present tense) was covered in the Introduction to Verbs unit. You can find it near the beginning of the A1 section here: https://www.practiceportuguese.com/units/main/

You can also practice individual verbs in the Verbs section here: https://practiceportuguese.com/verbs

Great site, this is exactly what I was looking for to learn Portuguese. I’m really enjoying it. Question about talking to strangers:

Suppose I’m in a restaurant and want to ask for the check. I could say “Quero a conta, por favor” but could/should I instead say, “Quero a conta, senhor” or maybe “O senhor, quero a conta” or maybe even “O senhor, quero a conta, por favor”? Would it make any difference if the person is older or younger than me? My inclination is to try to be as polite as possible with strangers, but I suppose one could stack on so many politenesses that it would start to sound a bit silly to them and I don’t quite know where to stop piling them on.

Thanks you so much for your kind words, John!

First of all, if you’re a foreigner making the effort to speak Portuguese you will NEVER sound silly! So, get that out of your way and just go for it.

Second, when asking for the check you don’t need to use the “senhor”, but I would recommend to avoid the “quero”. It sounds a bit too bossy, direct/imperative. Same as in English, you wouldn’t say “I want the check”, would you? It’s better if you use something like “Pode trazer a conta, por favor?” = “Can you bring the check, please?”/”Can I have the check, please?”.

Whichever phrase you choose, you can never go wrong with the “por favor”/”please”! 🙂

Hi there,

My hubby and I have just started a Portuguese course for foreigners at a local high school. I’ve been plodding through your lovely course for over a year now, but hubby has done nothing yet. So we decided to start a course together… OH DEAR. First lesson last night teacher introduced vós and I think basically said you cannot use você and vocês… So I am really confused.

I have not as yet seen or heard vós in any context… but then that could very well be me!!

I much prefer your explanation of pronouns and their degree of formality which was clear and straight forward. Now I feel cut adrift and unsure when to use vós? Any help much appreciated.

Olá!

Officially, “vós” is our true second-person plural pronoun and it’s the only pronoun you’ll usually see in formal verb conjugation tables. “Você” and “vocês” are not formally accepted as standard personal pronouns, and in that sense, your teacher is correct. However, in practice, “vós” has fallen out of use in most of Portugal, save for certain specific contexts (e.g. liturgy) and some regions, mostly in the north, where it’s still commonly heard. Otherwise, “você” and “vocês” have largely taken over, and in a significant portion of the country, it’s all you’ll ever hear people use in everyday life. It’s possible that your teacher simply failed to add this context to their comment.

Considering the now limited use of “vós”, and also knowing how challenging it is to conjugate verbs with “vós”, here at Practice Portuguese, a choice was made to unburden our members and focus only on what would be of most direct use to them: teaching “você” for the formal second-person singular, and “vocês” for the second-person plural. Even in the regions where “vós” is present, the use of “vocês” is also perfectly acceptable, so it’s something that people can use anywhere without concern and without any greater difficulty, since the conjugations are the same as those of third-person singular and plural pronouns (ele/ela/eles/elas). This is why you haven’t seen it covered in our materials so far 🙂

Joseph, thank you so much for taking the time to explain so clearly. I fully understand. PP’s structure is much more logical to me and echoes my knowledge of German!! Well I am off to be burdened. thank you once again 🙂

Of course, you’re welcome! Good luck with your classes 🙂

Olá

Thankyou for clearing this up ! I was wondering why I couldn’t find any resources on “Vós” I have family in North from Guarda who are helping me along with my Portuguese and Friends in the Algarve who take great joy in correcting my grammar and one friend from Angola helping me along also and there is much debate over the use of Vós lol !! My friend from Angola is determined that I learn the use of it and how to conjugate with it.. Keep the language alive he sais… The joys of learning 🙂 !!

Enrico,

“Keep the language alive (by using vós) he sais”? In good humor, you’ve been speaking too much Portuguese! He “says” not “sais.” LOL. I also am forgetting some of my native English already!

This is a great guide, thank you!

I have also seen in another Portuguese course that it’s possible to hear the words “sô” and “sora” as shorter forms of “o senhor” and “a senhora”. I actually haven’t encountered these, so I would guess these forms might be less common.

Would you advise using them? Maybe in a less formal context?

That is correct! Those forms do exist. However, it’s just a “nice to know” thing. It’s almost like slang! For someone learning the language, we would only advise you to use the normal terms: Senhor and Senhora.

It is also kind of common to hear expressions such as “Sotor” and “Sotora” which are short for “Senhor Doutor” and “Senhora Doutora”, respectively.

As an American, “voce” is very difficult to get comfortable with. For Americans, this degree of formality would be considered the opposite of polite, and indeed very rude — it’s as if you’re saying “I don’t want to be friendly to you (implicitly, because I don’t like you).”

A Nigerian co-worker of mine uses “A Senhora+first” name when referring to his superior. For example “Miss Violet”.

Thank you for explaining with flow chart and examples with the pronunciation, I really love this learning with you.

Would it be considered offensive to use você to reflect a question back to somebody in a relatively formal environment.

For example, a relative stranger asks you:

“Como está?”

Is it acceptable to reply

“Está tudo bem, obrigado. E você?”

Or is it safer to repeat the whole question back to them?

Thanks!

Using ‘você’ is not offensive by default, but it’s true that some people might find it rather blunt. If you want to be on the safe side, you can replace ‘você’ with ‘o senhor/a senhora’:

– Está tudo bem, obrigado. E o senhor/a senhora?

After saying ‘tudo bem’, you can also just use ‘E consigo?’, which is also foolproof and has the bonus of applying to all genders:

– Está tudo bem, obrigado. E consigo?

This is probably the most frightening aspect of learning Portuguese. I can power through conjunctions and memorize vocabulary. I can even work out the countless exceptions to the rules. However, I will never feel really comfortable with a formalized social stratification. I’m sure that’s because I’m American and would address anyone, from the family cat to the president, as ‘you’. I think this may be related to the difference in the Hofstede power distance between Portugal and the US.

Why are some verbs separated by “de” (gosta de ler) and others are not (quer comer)? I kept getting the practice question in this section wrong because I didn’t know when to use “de.” Thanks!

The use of de usually depends on which verbs are being used. Verbs that require this preposition include gostar and lembrar, so whenever you have these verbs followed by an object/complement, you will need to include “de” at the start of that object/complement. Verbs such as esquecer also usually take this preposition, although not strictly mandatory:

– Eu gosto de sopa. (I like soup)

– Tu lembras-te de mim? (Do you remember me)

– Ela esqueceu-se da data. (She forgot the date) (‘Ela esqueceu a data’ is an acceptable alternative)

I’m afraid I could not find a specific reason for this! 🙂

Oh no! I thought I was being polite by using voce! Thanks for helping me to avoid that faux pas in the future.

How do these levels of formality compare to the use of “usted” in Spain? Like vocês, it’s conjugated in the third person, and we normally omit the subject (just as we would omit any other subject, including “tu”, because it sounds too emphatic/aggressive). Growing up I was taught to use “usted” for anyone older than me, which nowadays translates to a) middle-aged strangers, b) the elderly, c) shop assistants etc. This seems about right for the “elided subject” use: “Quiere um café?

“A senhora” is hard to get my head around, as we used to use the equivalent expression, but it’s very outdated today and sounds excessively formal, even mocking. I think perhaps the equivalent over here might be including “usted” in the sentence, e.g. “Si quiere usted darme su teléfono…” (thinking of your car accident example) though it can definitely also be used more aggressively.

Has the use of formal treatments changed over the past few decades? In Spain, “usted” is on a fairly fast decline, and older people quite often tell me not to use it, even getting a little offended if I slip back in out of habit. (My primary school teacher was very insistent, and the habit stuck.) I’m curious if there’s anything similar happening in Portugal.

Muito obrigada 🙂 I realise trying to translate cultural things like formality is often a futile exercise, but it’s still fun!

Olá! Hard to make a direct comparison. I would assume that the Spanish “usted” is comparable to most of our formal options, except for “o senhor”/”a senhora”, which might surpass “usted” in terms of formality.

I think if we look back over the past few decades, we’ll notice shifts in some aspects of the spoken (and written) Portuguese language. But the use of formal treatments seems to remain relatively steady, especially among people of higher socioeconomic status 🙂

I commend you for doing such a great job. Your approach beats 90% of other apps out there. As a tech founder, it takes a lot of hard work and dedication to get where you are. Congratulations! Keep it up!

Thank you.

Haas

Olá

As an Australian where we tend to be far less informal (e.g. we often refer to a medical doctor by their first name let’s say “Ben” or it seems very rarely as Dr Harrison). And as someone with a PhD most of my students addressed me by my first name. The portuguese differentiation is going to take some getting used to. Just as well I have given myself years to learn the language.

By the way is there anyway of making the comments section show the latest ones first? And also not to have to scroll right to the end to reach the comments box?

Obrigado.

Hello.

Question about vocês, do we treat it the same as você and avoid using it to not sound aggressive?

Or is vocês okay to use?

No, vocês is not treated the same way as você! Vocês can actually be too informal in more formal contexts.

Here’s the Learning Note on this for a better understanding:

https://www.practiceportuguese.com/learning-notes/formal-informal-treatment/

🙂

This is surprisingly almost the same as Japanese! You don’t usually use the most honorific / formal form unless deliberately trying to establish distance, and usually just replace it with titles / the other person’s name + “san” / nothing. Guess I’m having an easy time with this :))